Bordeaux was in terrible shape at the end of the Second World War. It had been occupied by the Germans, and cellars were destroyed or looted. Vineyards were in poor condition: the women had done their best to maintain them and harvest grapes during the war. But the summer of 1945 was glorious and harvest occurred in close to perfect conditions. A frost early in May had reduced yields and increased concentration. The wines proved to be the best vintage of the twentieth century. Its only rival might be 1961. It’s generally agreed that the Médoc was the star of both vintages. The rivals for the best wine of the century divide between Mouton Rothschild 1945 and Latour 1961.

At a retrospective in New York to celebrate the 80th anniversary, the vibrancy of the wines was still evident. Opening with Trotanoy, the wine still seemed fresh with lively fruits, well rounded, and just a touch of the tertiary character of old Merlot. It did not fade at all in the glass, even over an hour. Its elegance might be viewed as a contrast with the sheer power of today’s Pomerols.

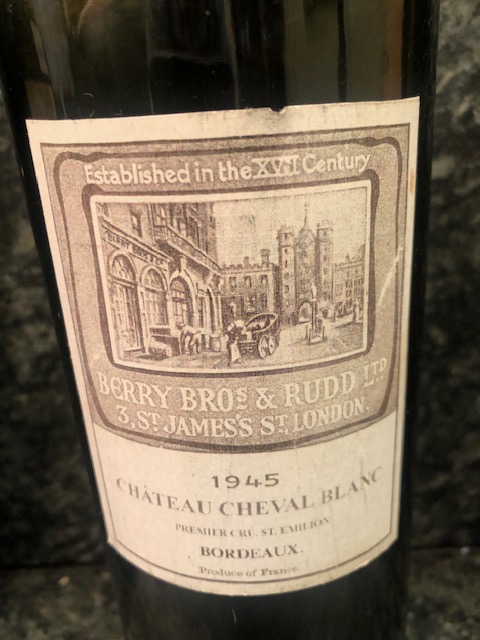

The Berry Bros bottling of Cheval Blanc followed. It’s well known that Cheval had problems with over-heating in the vats in 1945, with ice thrown in to cool some, and volatile acidity sometimes developing. There was no trace of either problem with this bottle. Indeed, this is one of the rare instances in which I have usually found the Berry Bros bottling to be superior to the chateau bottling. The flavor spectrum of Cabernet Franc was marked, with that dry sense of tobacco dominating the finish. The wine held up well immediately after opening, but faded a bit after half an hour as the dryness of the finish took over.

The next two flights were comparisons. Lafite Rothschild has been ethereal, with fragrant fruits floating in the atmosphere, but has begun to fade in the past couple of years. Although usually sturdier in most vintages, its neighbor Cos d’Estournel has sometimes shown something of the same fragrant elegance. On this occasion, the Cos started out if anything more fragrant and elegant than the Lafite, but first growth character showed as the wines developed in the glass and Cos developed an edge while Lafite floated along.

A similar development ensued with a comparison of Palmer and Chateau Margaux. Chateau Palmer started out with a touch more generosity, with rounder fruits, while Margaux seemed a little tight. Then as Palmer lost its sense of forward fruits, the structure of the Margaux loosened up and it become more elegant than the Palmer. The difference was a brilliant demonstration of the characters of their blends, heavily Cabernet Sauvignon for Margaux, more Merlot in Palmer.

Even after eighty years, Chateau Latour showed the power of Pauillac. Fruits are still relatively dense. Black fruit character and the pulling power of Cabernet Sauvignon remain evident. Some people preferred the Latour to the Mouton Rothschild, but I thought the Mouton pulled ahead for slightly livelier fruits, greater aromatics, and sense of freshness. It really is a timeless wine, or at least as timeless as wine can get.

We finished with Chateau d’Yquem, so dark it seemed almost black. All Sauternes become darker with age, of course, but they say at Yquem that the 1945 is one of the darkest of the vintages of the century, having taken leaps into greater darkness every decade. It was even more intense than I remember it from my previous tasting, twenty years ago. The balance of sweetness to acidity is fantastic, with a palate that’s mature but not old, and a huge range of flavors.

I suppose it’s undeniable that these wines are no longer at their peak, which in most cases may have been several decades ago, but they are a living demonstration of the greatness of old Bordeaux.

Detailed Tasting Notes

Trotanoy

Pungent notes of old Merlot show through sweet ripe fruits, still in balance with acidity. Not at all tired although tannins are resolved. Keeps going in the glass and does not tire at all.

Cheval Blanc

Strongly dominated by mature Cabernet Franc with notes of tobacco and tea on the finish. Quite dry at the end. Feels more like the seventies than the forties in terms of age. Fading a little in the glass as fruits begin to dry out. A faint touch of tannin at the end becomes bitter as the fruits fade.

Cos d’Estournel

Just a little less weighty than the Lafite, but a very similar impression of elegance. Sweetens in the glass after opening, and then becomes a little bitter as it develops, losing elegance compared to the Lafite.

Lafite Rothschild

Not as fragrant or aromatically uplifted as previous bottles. A little sturdier than Cos when it opened, with a touch of bitterness at the end. But lightens up in the glass, developing that infinitely fragrant elegance.

Margaux

Very refined, greater sense of precision in its black fruits than Palmer, very much Cabernet Sauvignon in fine structure and texture. Great finesse Fruits begin to dry out very slowly in the glass.

Palmer

At first the Merlot carries this forward with a sense of generosity. A little fleshier than Chateau Margaux to begin with, but becomes a touch bitter as fruits fade in the glass.

Latour

Ripe and generous and quite nutty on the finish. A touch of bitterness as wine develops in glass. Certainly full bodied, you can definitely see the power of Pauillac and Latour, but it’s lost the sheer gloss, the plushness, that it showed when younger.

Mouton Rothschild

A little nutty, a little more elegant than Latour. Something of the same sense of those fragrant layers of flavor, that ethereal character, of the Lafite, but weightier. There is now a little bitterness on the finish.

Chateau d’Yquem

Rich, unctuous, figgy, very intense, very viscous. Notes of caramel. Sweet but not overwhelming. Very much its own wine, its own style. Vastly more complex than a modern Sauternes.