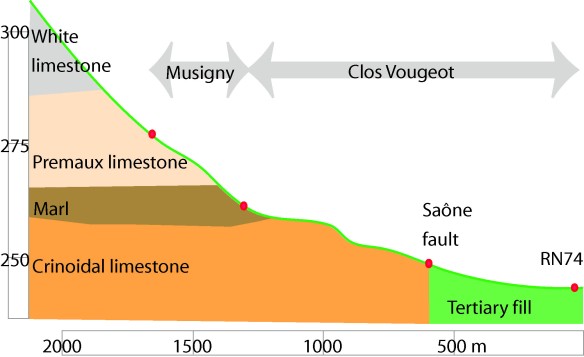

Clos Vougeot is perhaps the most variable of all the grand crus of the Cote de Nuits, and the one whose status is most often questioned (Echézeaux being the other). It’s only the accident of the area being literally enclosed by a surrounding wall that led to the uniform classification, as it extends right from the top of the slope (more or less in line with the premier crus) through the middle (in line with the grand crus) to the bottom (usually mere communal territory). In fact, it’s worse than that, because the fault line that mostly runs along the N74, dividing the great communes from the mere Bourgogne on the other side, actually diverts to run through the bottom edge of Clos Vougeot. (I discuss this in detail in my book In Search of Pinot Noir, from which the figure below is taken). Classified by geology, Clos Vougeot would include everything from ordinary Bourgogne to Grand Cru. Now if you taste your way across, for example, Gevrey Chambertin, from say the N74 to Le Chambertin, the difference between communal appellation, premier cru, and grand cru is usually fairly obvious. An unusual opportunity to see if there are obvious differences with location for Clos Vougeot came from a tasting of the 2011 vintage organized by Fine and Rare Wines in London, with examples from 38 producers.

A cross-section of Clos Vougeot shows the strong variations in terroir.

Clos Vougeot has been divided between many producers since the French Revolution, but its division into climats hasn’t changed much since the sixteenth century. The monks knew all about this, and supposedly used the wine from the bottom for communal use, the wine from the top for visiting bishops, and reserved the wine from the middle for princes and the pope. Most of the wines at the tasting represented one of these three areas, but some were blended from multiple plots. However, the striking feature was a lack of any clear correlation between location and style.

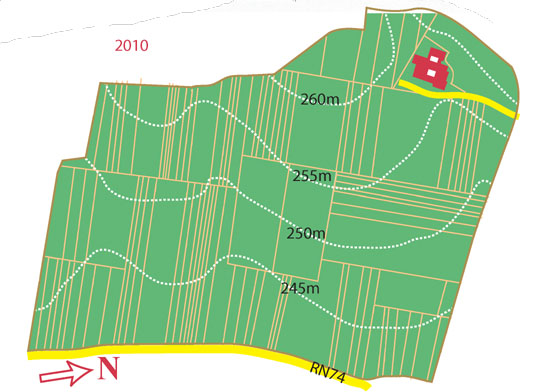

Clos Vougeot is divied into many plots with around 80 proprietors.

Clos Vougeot is divied into many plots with around 80 proprietors.

For me the wines of character fell into two general groups, which roughly might be defined as those I would (mistakenly) have placed in the Cote de Beaune in a blind tasting, because flashy red fruits showed more than structure, and those that I would unhesitatingly have placed in the Cote de Nuits (sometimes farther north than Clos Vougeot). Perhaps there is a tendency for the wines from the bottom to show more overt fruits and those from the very top to show more obvious structure, but I’d be hard put to support that in a blind tasting.

Clos Vougeot may offer the most fleshy character of the Cote de Nuits, certainly more opulent than delicate Chambolle Musigny or stern Gevrey Chambertin. I was really surprised by how sweet and ripe many of the wines were, although that’s not the reputation of the 2011 vintage. I was frankly disappointed by about half the wines, which seemed to lack grand cru quality (meaning that fruits were relatively simple and I could not see where future complexity would come from), but these showed no correlation with position, and came from plots all over the Clos. (It’s true that none of my preferred wines came exclusively from the bottom, but I don’t think that’s statistically significant.)

Wines in my category of delicious but rather Beaune-ish, with red fruits dominating, include Chanson, Chateau de la Tour, Louis Max, Denis Mortet, Mugneret-Gibourg, Jacques Prieur, Drouhin, Roche de Bellene, Domaine de la Vougeraie, Chauvenet-Chopin. Nice wines, but shouldn’t we expect more from a grand cru than simply a delicious crowd-pleasing quality?

Wines that melded the fleshiness of Clos Vougeot with a sense of structure of the Cote de Nuits, with black fruits more prominent, include Jean-Jacques Confuron, Louis Latour, Marchand-Tawse, Domaine d’Eugénie, Anne Gros, and the Vieilles Vignes from Chateau de la Tour (quite different from the regular cuvée). This is my concept of Clos Vougeot, anyway.

Some top wines came from old-line producers. Méo-Camuzet, including a large prime plot close to the chateau, really showed as a classic grand cru from Cote de Nuits, Arnoux-Lachaux (from plot in the upper third) a nice mix of fleshiness and structure in the modern style of the house, and Louis Jadot (from a plot extending from bottom through the middle) showed their characteristic sense of balance.

It is a sign of the times that I thought two of the best wines came from micro-negociants who do not even own any land in the Clos. Olivier Bernstein showed his usual opulent style, but with enough underlying structure to support longevity for years. The wine lives up to the reputation of the plot, which has very old vines (more than 80 years) in the middle of Clos Vougeot towards the south. The wine I found the most interesting of all came from Lucien Le Moine, and is not identified with any single plot. “Our Clos Vougeot has a particularity, it’s a blend from all three parts,” winemaker Mounir Saouma told me on a recent visit. The monks would have been very pleased with this: it captures the fleshiness of Clos Vougeot in the context of the structure of the Cote de Nuits and Mounir’s trademark elegance.

The take-home message for me was that producer triumphs over terroir in Clos Vougeot. Should it be a grand cru? I’d say about a third of the wines met my standard for grand cru. I’ll have to do a similar tasting for Chambertin or Musigny to see if the ratio goes up.

So, does Clos Vougeot have the same problem as Schlossberg? And how many other famous names are too big in area for consistent high quality?

I suppose you might say so in a way, although at Schlossberg the reason for expansion was to satisfy local politics (including important people who owned some of the plots), whereas Clos Vougeot has always been regarded as a whole because of its enclosure, so calling it all grand cru is somewhat following history (rather than geology). Echezeaux, as I mentioned, is another example, this time clearly because of politics (if I remember correctly, some attempts to restrict Echezeaux and Grands Echezeaux were defeated by legal action in the thirties). Corton would be the third example; it is pretty clear that some of its climats are grand cru quality but others are not. Perhaps there would be an argument for saying that, given how rapidly the soil changes in Burgundy, no area as big as any of these three could have the consistency to justify being grand cru tout court.

Pingback: Killer Clos Vougeot Map - SpitBucket